It is unfortunate—but it is a fact—that some Ethniks, both white and Negro, already are referring to the prospective national final as not just a game but a contest for racial honors.

That’s how Frank Deford of Sports Illustrated described the prospect of Texas Western (now known as University of Texas at El Paso) playing in an NCAA final against the all-white teams of Kentucky or Duke. And it happened almost 50 years ago to the day.

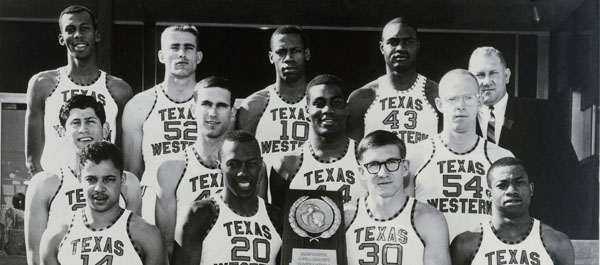

On March 19, 1966 during the NCAA National Championship, five black players stepped onto the court at Cole Field House, where they not only won a championship but paved the way for thousands of black athletes.

Why The Game Was Important…

In 1965, just a year earlier, Malcolm X was assassinated, the streets of Selma turned red with the blood of peaceful protesters and The Voting Rights Act was signed into law. But by 1966, civil rights leaders like SNCC chairman Stokely Carmichael were becoming increasingly impatient with the nonviolent approach.

That was the social climate.

And race played a factor in how athletes were viewed. At the time, conventional wisdom said blacks were great athletes but weren’t smart players. You could use blacks as rebounders but not as point guards (and certainly not playmakers). As a contender to the national championship, Texas Western’s team, led by an all-black starting five, would test that convention.

The Man Behind The ‘66 March Madness

In his autobiography, Glory Road, Texas Western coach Don Haskins explained that line of thinking and how it played out in football also—blacks weren’t supposed to be smart enough to play quarterback either. The thing is, he didn’t buy into that ‘conventional wisdom.’

“It never crossed my mind that a guy who was black could never run a team. I think a lot of my beliefs went back to playing with Herman Carr (Haskins’s African American childhood friend). He knew the game better than I did for a long time. I learned from him,”

The Not-So Happy Ending

Texas Western, now the University of Texas at El Paso, beat the all-white Kentucky team 72 to 65 for the championship. After such a landmark win like, you would think the story would end in a “happily ever after” conclusion for both sports and race relations. But that wasn’t the case.

After the game, hate mail started arriving by the boatload. By one estimate, coach Haskins received 40,000 letters.

One well-known writer described the win as “one of the most wretched episodes in the history of American Sport” and then went on to describe the Texas Western players as criminals and nonstudents.

The following season, the team even had to play a game against Southern Methodist University under the protection of the FBI because they received so many death threats.

How the Color Barrier Broke

Despite the unfair media coverage and a country that had pretty much turned against them, the players of the ‘66 team went on to become executives, educators, coaches and the like. So in the end, the players had the last word because they got their education. And because of that game, there were more opportunities for black players across the country.

The era’s conventional wisdom about black athletes could no longer be firmly upheld with an all-black starting five, NCAA championship team.

“Before we beat Kentucky there was not a single black basketball or football player in the Southeastern, Southwest, or Atlantic Coast Conference. Within five, six years everyone was recruiting black players, because if they didn’t, they wouldn’t be able [to] field a competitive team.” – Coach Don Haskins, Glory Road

Former Arkansas basketball coach Nolan Richardson credits coach Haskins for being responsible for “thousands of scholarships for blacks in the South.” And Chuck Foreman, a five-time NFL Pro Bowler, once stopped Coach Haskins in the airport to thank him “for giving black guys like him a chance to go to school.”

When Athletes Talk, People Listen

Even to this day, the influence athletics and athletes plays in society is without question. Case in point, #ConcernedStudent1950 and the University of Missouri (Mizzou) football boycott.

In a video by the Washington Post, a reporter explains the spike in media coverage. Prior to black football players boycotting, fellow Missouri student Jonathan Butler’s hunger strike was a regional story. But once the football team united and joined the cause, all of a sudden it was national news.

Two days later, the President of Mizzou resigned.

A Mizzou Mom’s Perspective

We hear about the schools, the players and the coaches, but have you ever thought about how parents feel? I was curious. So I sat down to talk with Laquita Stribling, mother of a Mizzou player.

Before the Mizzou story broke, she got a phone call. Her son was calling to explain why the football team was boycotting, even though they were personally treated well.

“My initial thought was ‘Okay, he’s officially entered manhood.’ But I was so proud of him because I didn’t know he had any social consciousness,” she says. “But he told me, ‘We see the injustice, and we’re taking a stand.’ And I was just so proud of him because he was thinking outside of himself.”

One Correction To The ‘66 History

Coach Haskins credits Texas Western player Willie Brown and New York City playground director and summer league coach Hilton White for thinking outside of themselves. Both men had families, careers and their own lives, but they spent free time, helping the kids in their neighborhood get scholarships to schools that recruited black players.

“I get a lot of attention for being the first to start five black players in a game. But if it weren’t for all of the leaders in the black community who helped send kids to me it never would have happened. There were countless heroes…and I thank them all.”

The Gift of El Paso, Texas

Another unsung hero in this story is the city of El Paso and its citizens. The University of Texas at El Paso, formerly Texas Western, integrated in 1955—the year after Brown v. Board of Education. And I think their early integration was one of the reasons the ’66 Team flourished.

Researching this story has made me proud of my familial ties to El Paso. My granddad moved to El Paso in the 1930s on a cotton pick, my dad grew up there and so did my husband. Not to mention, I attended UTEP for graduate school.

The kindness of El Pasoans is what kept Don Haskins at UTEP until he retired in 1999. He lived there until his death in 2008.

If you are a native El Pasoan, you probably know this story by heart. But if you want to learn more about the ’66 Team, Don Haskins and the city of El Paso, Texas, read Glory Road or watch the movie.

BMWK: What other moments in sports history had an impact on us as a people?

Leave a Reply